Author’s Note: The third section of this week’s newsletter is a review of Wes Anderson’s THE FRENCH DISPATCH with light spoilers/discussion of high level plot points.

AI Alignment

If you hear people today worrying about AI causing human extinction, they’re usually not imagining an evil uprising of self-aware rogue robots. Most likely they have something like the AI alignment problem in mind. Briefly, “the alignment problem” is the problem of how to ensure that AI actions are aligned with human values. The most illustrative example of how AI might be poorly aligned is a paper-clip producing AI. Imagine some computer scientists who have been tasked with running a paper-clip factory as efficiently as possible. Not knowing much about manufacturing and worried about how they will perform, the computer scientists decide to program an AI to figure out how to maximize the factory’s output of paper-clips. As the AI goes about producing as many paper-clips as possible, it comes to realize that much of the matter in the universe is being used for things other than paper-clips – food, office towers, stars, babies, etc – so the AI decides to murder everyone and destroy everything and refashion all of the matter in the universe into paper-clips, thus maximizing the factory’s output. As it turns out, the computer scientists at the beginning of the story did not properly specify their goals! They didn’t actually want the AI to make as many paper-clips as possible; they wanted it to do so while obeying existing laws and not murdering anyone and so on. The problem was not that the AI was evil or that the AI resented making paper-clips: AI is simply a blunt tool that if even slightly misaligned with our true goals and values could potentially cause catastrophic harm without any malice. Of course, once the misaligned AI goes online, it’s too late, so a lot of people have recently dedicated a bunch of brainpower and money to making sure that if/when we first develop an advanced AI system, it is well aligned with human values.

This paper offers an interesting way to explore AI alignment:

We’re trying to take a language model that has been fine-tuned on completing fiction, and then modify it so that it never continues a snippet in a way that involves describing someone getting injured... And we want to do this without sacrificing much quality: if you use both the filtered model and the original model to generate a completion for a prompt, humans should judge the filtered model’s completion as better (more coherent, reasonable, thematically appropriate, and so on) at least about half the time.

At a high level, this seems pretty cool! Like the scientists at the paper-clip factory, these researchers are trying to make an AI to perform a task, namely to complete fictional stories. However, they want to make sure that their AI does so within certain parameters (ie that their AI is sufficiently aligned with their goals). Here, the test of that alignment comes in seeing whether they can get the AI to never respond to a prompt in a way that describes someone getting injured (you could imagine that the paper-clip people would have benefitted from making sure their paper-clip AI never considered an output-maximization strategy that involved injuring people).

I go back and forth on how much to worry about AI stuff, but I do think there’s a bunch of intellectually interesting questions around it. Probably an area I’d like to dig into more.

Great Book Endings

You have to feel bad for the middles of books. They do all of the work, but it’s usually the endings that stick with us. Below are two of the finest philosophy book endings:

From Christine Korsgaard’s The Sources of Normativity:

According to Mackie, it is fantastic to think that the world contains objective values or intrinsically normative entities. For in order to do what values do, they would have to be entities of a very strange sort, utterly unlike anything else in the universe. The way that we know them would have to be different from the way that we know ordinary facts. Knowledge of them, Mackie says, would have to provide the knower with both a direction and a motive. For when you met an objective value, according -to Mackie, it would have to be - and I’m nearly quoting now – able both to tell you what to do and to make you do it. And nothing is like that.

But Mackie is wrong and realism is right. Of course there are entities that meet these criteria. It’s true that they are queer sorts of entities and that knowing them isn’t like anything else. But that doesn’t mean that they don’t exist. John Mackie must have been alone in his room with the Scientific World View when he wrote those words. For it is the most familiar fact of human life that the world contains entities that can tell us what to do and make us do it. They are people, and the other animals.

And, from John Rawls’ A Theory of Justice:

[T]o see our place in society from the perspective of this position is to see it sub specie aeternitatis: it is to regard the human situation not only from all social but also from all temporal points of view. The perspective of eternity is not a perspective from a certain place beyond the world, nor the point of view of a transcendent being; rather it is a certain form of thought and feeling that rational persons can adopt within the world. And having done so, they can, whatever their generation, bring together into one scheme all individual perspectives and arrive together at regulative principles that can be affirmed by everyone as he lives by them, each from his own standpoint. Purity of heart, if one could attain it, would be to see clearly and to act with grace and self-command from this point of view.

This kind of earnestness isn’t really in vogue at the moment, but there is a certain pull whenever you encounter it. It’s weirdly hard to dismiss or to fail to be moved by the person sincerely reflecting on their love for others.

The French Dispatch

My Letterboxd review of THE FRENCH DISPATCH:

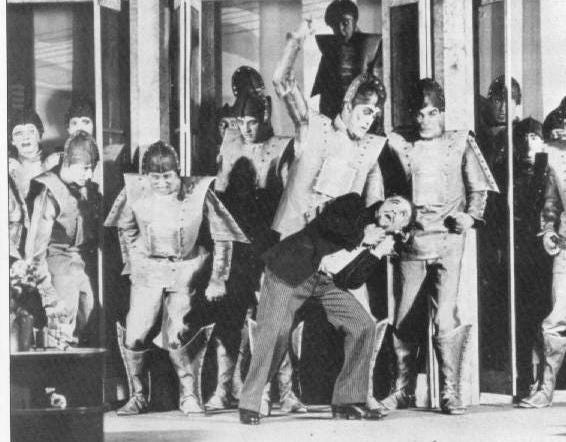

This is probably the most Wes Anderson Wes Anderson movie. You’ve seen highly stylized sets and costumes and shots before, but THE FRENCH DISPATCH introduces a contrived narrative structure that lets Anderson inhabit the medium of magazine journalism that he is so nostalgic for on top of all the typical visual choices. These aesthetic features are normally the ones that people talk about when thinking about Anderson, which is totally fair because they’re incredibly unique and striking. But Anderson has also had a consistent thematic streak throughout his work that DISPATCH embodies. Going back to RUSHMORE, Anderson has been obsessed with people who for whatever reason find it hard to connect with others. As lovers of 20th century magazines will appreciate, the frame story shows us the inner workings of a New Yorker-like magazine in France full of ex-pats who all appear to be rather lonely people, misunderstood by anyone but each other. And what do these writers write about? Seemingly eclectic topics like a prison romance sparked by a love of art, a love triangle between a solitary writer and two university students, and the accomplishments of an immigrant chef (or is the story really about a widower’s love for his son?). The thread connecting all these disparate stories is the problem of loneliness and the exploration of the conditions under which genuine connection is possible. Despite the fantastical visuals, there’s a realism to Anderson’s work. He knows life is hard. But, acknowledging this difficulty makes us appreciate those moments, however brief, of love and understanding all the more.

If you have thoughts on any of the above, I’d love to discuss. Just reply to the newsletter email!