Days of the Week

I saw an Instagram reel that was mocking English for supposedly having dumb names for the days of the week (“oh it’s Monday because ‘mon’ is like ‘mono’ and it’s the first day of the week, Tuesday because ‘tues’ is like ‘two’s’ for the second day of the week, but then what the heck is ‘Wednesday’?!”), but the way the days of the week are named in English is actually totally systematic and consistent with how it is done in a ton of other languages.

I first discovered this discussing the days of the week with a roommate of mine from India. For whatever reason, I was talking about my revelation that the French word for Tuesday (“mardi”) comes from the name of the Roman god Mars, the god of war and the namesake of the planet. My roommate, stunned, then explained that in Hindi, the name from Tuesday is “Mangalavār”, from the Sanskrit name for Mars and the god of anger who is also linked to the Hindu god of war. We then tested some other days, comparing French and Hindi. Wednesday in French is “mercredi”, which kind of sounds like “Mercury”; in Hindi, Wednesday is “Budhavār” from the word for Mercury. What at first seemed like a coincidence led to a google that confirmed it was no such thing.

According to the Names of the days of the week wiki, languages in the Greco-Roman, Germanic, Hindu, and East Asian traditions all use the same celestial body names for each of the days of the week. So the reel was wrong to look for numbers in the names “Monday”, “Tuesday”, and “Wednesday”, but how do any of those names connect to the words “Moon”, “Mars”, or “Mercury”? Ok the first one is actually pretty obvious: “Monday” is basically just “Moon day”. But where’s “Mars” in “Tues-” or “Mercury” in “Wednes-”? Isn’t weird that I was able to parse the etymologies for each of the days of the week in French with no problem, but I struggled with the English names?

My problem was that the days of the week in English do not correspond to the Roman names for the celestial bodies but to Germanic names. If you have some background in Germanic culture/mythology (which I did not and do not really have), you might think that “Tues-” sounds like “Tyr’s”, making “Tuesday” “Tyr’s day” or the day of the god that the Romans equated to Mars. “Wednes-” sounds like “Woden’s” or “Odin’s”, so you get “Odin’s day”, Odin being the god the Romans equated to Mercury. How quickly we forget English is as much a Germanic language as a Romance language!

There was a kind of condescension in the reel in saying that “Wednesday” sounded ridiculous. I’m not sure, but I would guess that a Germanic language speaker or someone familiar with Norse culture would hear the Woden/Odin thing in “Wednesday”, and it wouldn’t sound so ridiculous to them in the way that I could pick up on the connection to Ares/Mars in “mardi” in French.

Of course, the condescension towards Germanic-sounding English phrases is somewhat natural given how the language evolved. One interesting quirk of English, for example, is that we use Romance words for many of the meats that we eat (“beef” from the French “boeuf”, “pork” from the French “porc”, “mutton” from the French “mouton”), but we use Germanic words for the animals the meat products come from (apparently “cow” comes from Old English “cu”, “pig” from Old English “picg”, “sheep” from Old English “scep”). The theory goes that after the Norman invasion, the French aristocracy who feasted on meat influenced the words for the end-products, while the Anglo common-people tending the animals influenced the words for the living creatures. Who knows how accurate that is, but it does seem to neatly explain our current biases around the Germanic influence over English. A cool way to test how the Germanic aspects of English sound to you is to read something like Uncleftish Beholding, an overview of atomic theory largely written without names or words derived from Latin (so “uranium” from the Greek god Uranus becomes “ymirstuff” from Ymir, the name of a giant who plays a similar role in Norse mythology).

I’m not sure it matters that we’ve kinda buried the Germanic influence over English, and I’m as guilty of it as anyone, but I think it potentially says something interesting about how we conceive of ourselves. In my review of Against the Grain, I asked

What might we have lost in creating permanent settlements? How could our lives be different - better? - than they are? Who are the barbarians today and what might they see that we don’t?

Now, reflecting on our relationship to our language, I wonder: what is lost and what is gained in seeing ourselves primarily as the cultural descendants of Rome and not of those who resisted Rome’s influence?

Amor Scientia

Seen on Twitter:

Myopia

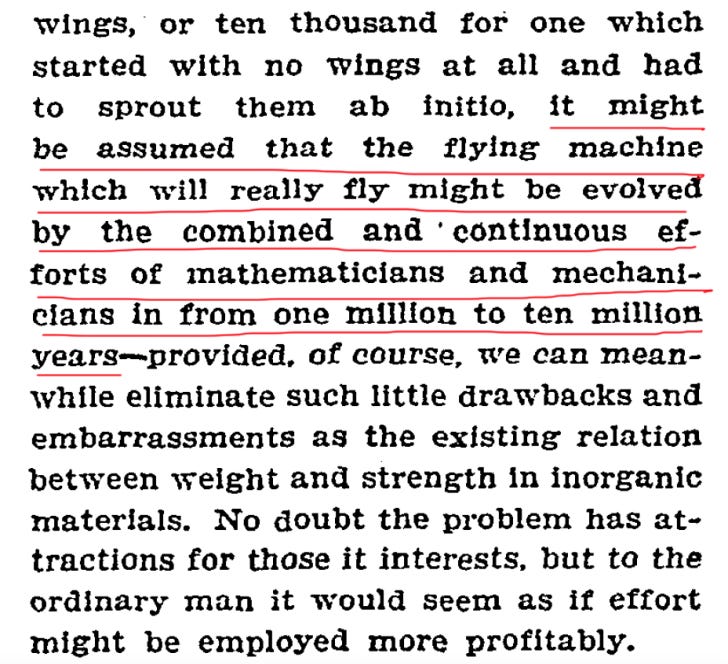

As the New York Times can attest, predicting the future is hard:

Compare with this 2004 Pitchfork review of Kanye West’s debut album The College Dropout:

Ironically, Kanye’s criticism of college looks incredibly prescient given how the last 17 years have shaken out with the student debt crisis and the rise of alternatives to college like the Thiel fellowship and Lambda School. Not that the reviewer should be held responsible for predicting those things – again, predictions are hard. But, there’s a close-mindedness in the phrase “strange logic” and to dismissing something out-of-hand by simply claiming it won’t age well, thereby deferring the responsibility for actually evaluating the thing to some future audience.

A lesson to learn from this is that in a world where predictions are hard and the only thing known about the future is that it will surprise us, curiosity and openness are critical.

If you have thoughts on any of the above, I’d love to discuss. Just reply to the newsletter email!