French Legitimacy; Newsletters; Dueling Narratives

10/21/2021

Author’s Note: The last section of this newsletter is a spoiler-heavy review of Ridley Scott’s new movie THE LAST DUEL. Would not recommend reading that section if you have not yet seen the movie.

Weber and French Legitimacy

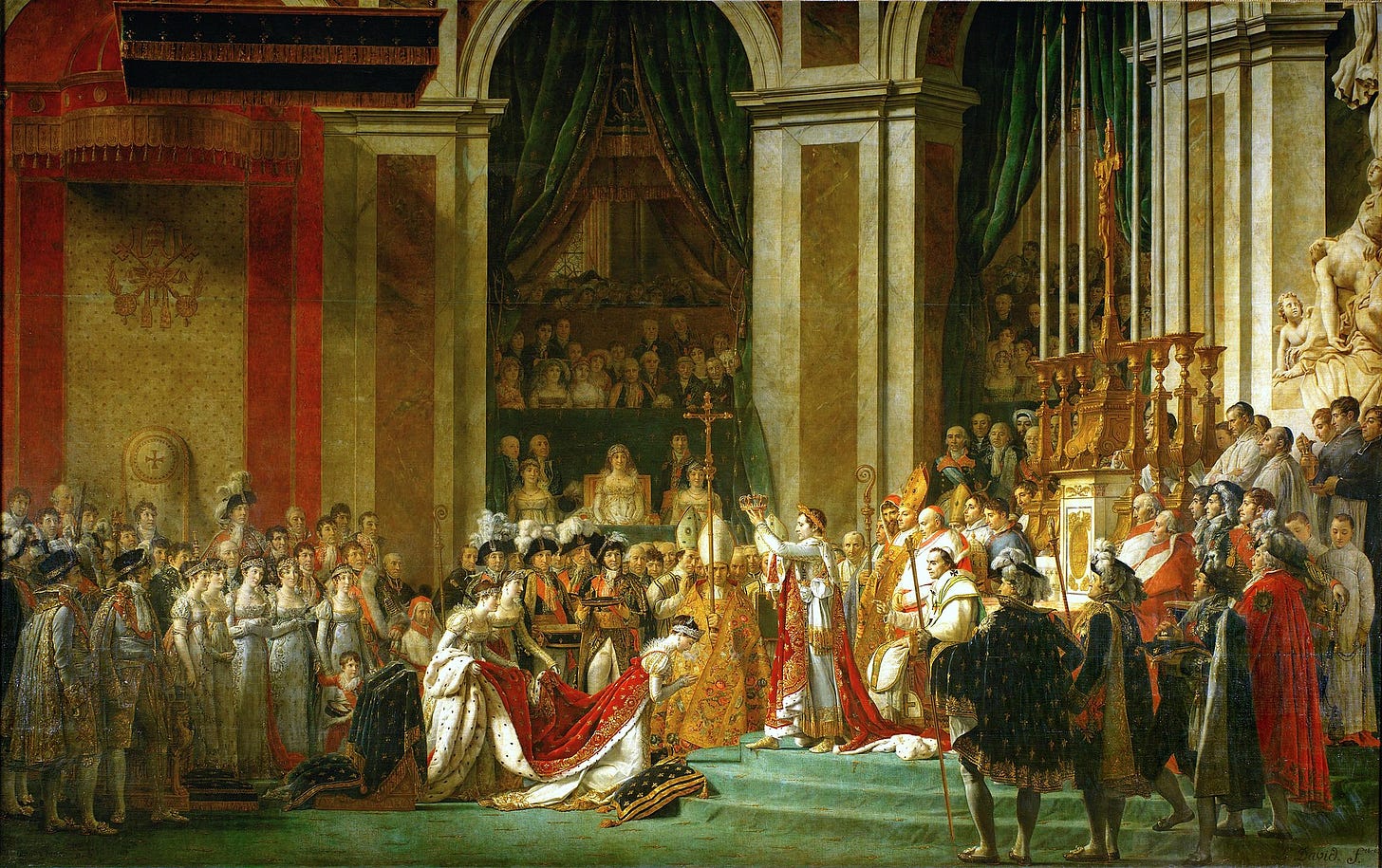

I’ve been reading Weber’s stuff on legitimacy and unrelatedly learning a bunch about early 19th century France (really enjoyed the Revolutions podcast season on the July Revolution and continuing to enjoy “Les Misérables” and “The Red and the Black”). Weber thinks there are three broad categories of apparently legitimate government: bureaucratic, traditional, and charismatic. I thought these three types mapped relatively cleanly to the three claimants to French rule: Orléanists, Legitimists, and Bonapartists. The Orléanists offered a bourgeois conception of stable and good governance; the Legitimists appealed to the nobility of an ancient tradition; and the Bonapartists were largely motivated by their admiration for the character of Napoleon. I’d be curious if there’s evidence that Weber had post-Napoleonic France in mind when he was coming up with his types. Perhaps an interesting way in which historical accident (ie that France happened to have claimants that fit into these three categories) can both illuminate and limit our understanding of a transhistorical concept like legitimacy.

Newsletters

Good writing is insanely powerful. I love reading Matt Levine’s newsletter even though I objectively should not - it is a financial news newsletter, and I do not work in finance nor am I particularly interested in finance. Levine just tells a really great story, and I like to be entertained. Incidentally, much like how PBS shows tried to incept math and language skills into your brain, Levine has implanted a bunch of knowledge about finance and law into my brain that I was not even looking for.

I kinda suspect a great writer could similarly make any number of other topics fascinating and educate a large audience on their niche interest. I’d be happy to read many such newsletters, but it’d be especially cool if the thing the newsletter was secretly teaching you was like cutting-edge biotech knowledge for curing terrible diseases and did so in such a way that motivated lots of young people to go study that stuff.

Dueling Narratives

Spoilers for THE LAST DUEL below!

My Letterboxd review of Ridley Scott’s THE LAST DUEL:

What does the narrative structure of THE LAST DUEL accomplish? I think the first instinct is to say that its a way to explore a he-said-she-said situation. Memory can be faulty and our experience of reality is inherently subjective and limited. Maybe what the movie was looking to explore is how there is no objective truth outside of the imperfect subjective experiences of different people. This explanation doesn’t quite work though because one of the vantage points is privileged. We know that Marguerite’s perspective is the truth. There are no “two sides” – she was raped by Le Gris. Instead, what I think the narrative structure serves to do is to expose the gap between the stories we wish to tell about ourselves and reality.

de Carrouges sees himself as a gallant soldier in the tradition of tales of knightly adventure. Le Gris sees himself as the star-crossed seeker of forbidden love. These men are so caught up in these romantic archetypes that the first two sections told from their respective perspectives almost feel like tonally different movies: the first a war story and the second a romance (and even at times romantic comedy). Unfortunately, as the third section of the movie reveals, the 14th century France our characters inhabit is not at all like a fairytale. The king of France is a child, his count is a womanizing alcoholic, the “heroic” soldier is more foolhardy than courageous, and our “romantic” is a rapist. Quite a bit is rotten in the state of France! In Marguerite’s version of the story, we learn that real life is not bound up in genre conventions. The villain does not confess his crime. The lord and lady do not live happily ever after. The stories society runs on are just stories, and our obsession with them obscures reality. Only Marguerite can see through the narratives and see her world for what it is: decadent and oppressive.

Though the structure of the film emphasizes the gaps between story and reality, I don’t think the film is simply an indictment of the deceptive quality of stories. The movie remains ambivalent on the value of stories. Though they draw our attention away from the truth, sometimes shared delusion is necessary for society to function.

Take the titular act of the movie: the last duel in French history used to adjudicate a criminal dispute. Obviously no one actually believes that winning the duel is proof of innocence. The king even admits to incorrectly thinking that such trials-by-combat had been made illegal before prescribing the duel as the solution to the dispute. No, a duel would not reveal anything true about the world, but it would give society a useful story to make sense of what had happened and move on. The duel leaves only one man to play the hero, and either France would be left with the noble husband defending his wife’s honor or the handsome self-made man who overcame the machinations of a jealous aristocracy. As Ben Affleck’s character observes, people are uncomfortable with nuance. The truth as told by Marguerite where both men are shallow and abusive could never work because it fails to give anyone a sense of resolution.

Or take the example of the depiction of the king of France. Everyone in the movie acts as if the king were some wise figure and not a mad child; after all, what good would there be in denying the narrative of the king’s sagacity? Surely acknowledging the truth is not worth fighting a bloody civil war to usurp the king. Marguerite poses a similar question about her own situation: what good is there in her speaking up about what she went through if it could mean her son growing up as an orphan?

On the one hand, the stories society runs on are lies. On the other hand, the lies we tell each other help society function. An inconvenient tension? Maybe. But the truth is often inconvenient.

If you have thoughts on any of the above, I’d love to discuss. Just reply to the newsletter email!