Modern Epics; Eating Shoes; Licorice Pizza

11/28/2021

Author’s Note: The third section of this newsletter is a review of Paul Thomas Anderson’s LICORICE PIZZA and contains some spoilers.

Modern Epics

In college, I took a great English class on the epic tradition. We traced the genre from its roots in Homer to Virgil’s reboot of the Homerian epics to John Milton’s Christian interpretation to George Eliot’s modernization of the epic and finally George Lucas’ adaptation.

When I read Eliot, I thought it was interesting how explicitly she states her project in the beginning of the book, making it easy for us non-English majors to understand what she was up to in Middlemarch:

Who that cares much to know the history of man, and how that mysterious mixture behaves under the varying experiments of Time, has not dwelt, at least briefly, on the life of Saint Theresa, has not smiled with some gentleness at the thought of the little girl walking forth one morning hand-in-hand with her still smaller brother, to go and seek martyrdom in the country of the Moors? … Her flame quickly burned up that light fuel, and, fed from within, soared after some illimitable satisfaction, some object which would never justify weariness, which would reconcile self-despair with the rapturous consciousness of life beyond self. She found her epos in the reform of a religious order.

That Spanish woman who lived three hundred years ago, was certainly not the last of her kind. Many Theresas have been born who found for themselves no epic life wherein there was a constant unfolding of far-resonant action; perhaps only a life of mistakes, the offspring, of a certain spiritual grandeur ill-matched with the meanness of opportunity; perhaps a tragic failure which found no sacred poet and sank unwept into oblivion. With dim lights and tangled circumstance they tried to shape their thought and deed in noble agreement; but after all, to common eyes their struggles seemed mere inconsistency and formlessness; for these later-born Theresas were helped by no coherent social faith and order which could perform the function of knowledge for the ardently willing soul. Their ardour alternated between a vague ideal and the common yearning of womanhood; so that the one was disapproved as extravagance, and the other condemned as a lapse.

Some have felt that these blundering lives are due to the inconvenient indefiniteness with which the Supreme Power has fashioned the natures of women: if there were one level of feminine incompetence as strict as the ability to count three and no more, the social lot of women might be treated with scientific certitude. Meanwhile the indefiniteness remains, and the limits of variation are really much wider than any one would imagine from the sameness of women's coiffure and the favourite love-stories in prose and versa. Here and there a cygnet is reared uneasily among the ducklings in the brown pond, and never finds the living stream in fellowship with its own oary-footed kind. Here and there is born a Saint Theresa, foundress of nothing, whose loving heart-beats and sobs after an unattained goodness tremble off and are dispersed among hindrances, instead of centering in some long-recognisable deed. [emphasis added]

In pre-modern times, you had heroes like St Theresa whose piety led them to seek martyrdom and to reform great religious orders. Eliot’s description of St Theresa recalls pius Aeneas whose piety steels him against the various obstacles on his way to founding Rome. However, as Eliot looks around provincial 19th century England, she doesn’t see any Theresas or Aeneases accomplishing “long-recognisable deed[s]”. Middlemarch, then, explores the possibility of leading a great life in an ordinary setting like the sleepy English countryside as opposed to on the shores of Troy or at the founding of Rome or in war against Satan (or in the struggle between the Jedi and the Sith).

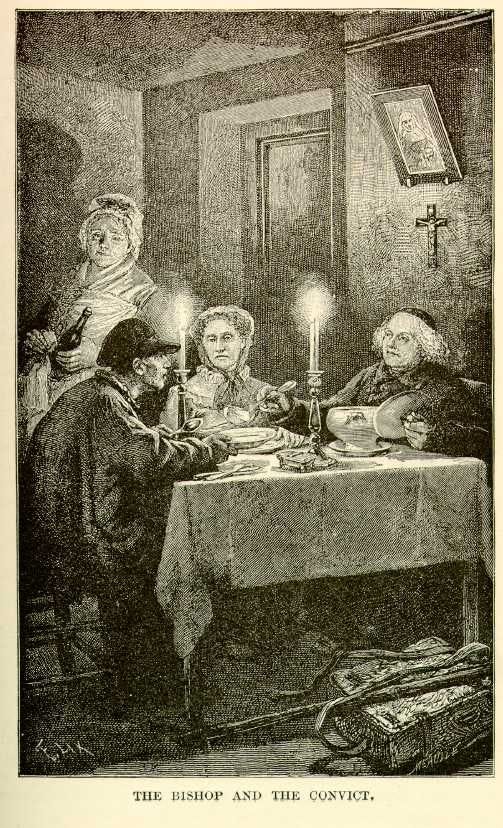

A couple of years after taking the class on epics, I started reading Les Miserables, which was written around the same time as Middlemarch and similarly explicitly situates itself in the epic tradition. At one point in the novel, Vitor Hugo literally just drops the story to argue that Les Miserables is the epitome of the epic:

To create a poem about the human conscience, were it only with regard to a single man, only to the least of men, would be to amalgamate all epics in one superior and definitive epic. Conscience is a confusion of chimeras, of desires and temptations, the furnace of dreams, the retreat of thoughts that shame us. It is a pandemonium of sophisms, it is the battleground of the passions. Probe, at certain moments, the ghastly pale face of a human being immersed in thought, and look behind it, look into that soul, look into that obscurity. There, beneath the outward silence, are battling giants, as in Homer, tumultuous dragons and hydras and phantom hosts, as in Milton, visionary vortices, as in Dante. What a solemn thing is this infinity that every man bears within him and against which he measures with despair the wishes of his brain and the actions of his life!

I was struck by how different Hugo’s take on modernity’s relationship to the epic is from Eliot’s. Where Eliot tells a story of decline from pre-modern to modern times, Hugo sees a continual progression in which his novel represents the zenith. Where Eliot sees modernity as a problem for greatness (ie “what’s a cygnet born among ducklings to do”), Hugo sees opportunity, almost seeming to say “oh you thought duels between semi-divine warriors was cool? Cosmic battle between the forces of heaven and hell? That’s nothing: wait till you see my story of a single wretched man finding his way from sin to grace”. They net out in similar places (roughly, it’s really great to be compassionate to those around you), but isn’t the Hugovian framing more inspiring? It’s easy to adopt a dialect of decline when discussing modernity, but there’s something exciting in seeing “battling giants… tumultuous dragons and hydras and phantom hosts” in modern life.

Eating Shoes

LICORICE PIZZA

If you haven’t seen the movie, I thought the trailer was fantastic:

My Letterboxd review:

Great performances from first timers Alana Haim and Cooper Hoffman (son of the late Phillip Seymour Hoffman, a long time PTA collaborator). Not sure this is what PTA was going for, but I couldn’t help but feel waves of patriotism watching the film. Isn’t Gary Valentine the epitome of the American spirit? He’s a young endlessly optimistic westerner full of energy constantly spinning up new businesses. He’s confident as an individual but his infectious charm brings together a community around him - a community in which misfits can thrive and build self-esteem around their unique talents.

Watching the trailer, I think you’d expect this to be the story of Gary’s coming of age, but he actually doesn’t change that much throughout the movie. He’s our constant source of optimism and confidence. Alana is the real star here, and the movie fundamentally traces her journey from aimlessness to purpose, self-love, and, well, love-love.

If you have thoughts on any of the above, I’d love to discuss. Just reply to the newsletter email!